From Wayfinding to Thingfinding

Written on 17 September 2010

Traditional wayfinding systems in the built environment typically provide effective support as we navigate our way to key destinations within a city.

This short treatise is about what they do not support.

The building blocks in any wayfinding system are the destinations the system directs us to; this is the raw data, without which there would be no need for the wayfinding system. A talk I gave at the

Information Design Conference last year, demonstrated how different methods of acquiring this data lead to quite diverse outcomes and subsequently to the development of wayfinding systems with varying levels of success for different people.

For example, when compiling a list of destinations, we may ask the client to provide the data, we may reference destinations listed on existing on-street signage, refer to destinations that appear on a map or site plan, or we can employ a user-centred design approach, conduct contextual research and find out from people in the street what destinations they are actually seeking.

Client representatives often have their own perspectives and agendas and they may not be able to understand, or be sympathetic to, visitors’ needs. A town centre-manager, in a city-centre wayfinding project I once worked on, felt it was his duty to look out for the financial welfare of local shop-owners. He wanted the retail district to appear as the key destination on all signs and the wayfinding system to direct all visitors to their destination via the retail district, even if that meant extending journeys by a considerable time and distance. Likewise, a tourism manager wanted all the main tourist attractions to make up the key directional information on signs.

What’s wrong with that, you might ask? Isn’t that what’s done everywhere? Well, perhaps, but commonly accepted ‘best practice’ isn’t always the best solution. The main tourist destinations are often well known and visitors can always ask locals for directions. When considering the limited amount of information signs can effectively communicate, it might be more helpful if signs included important destinations that not all locals would be able to point visitors towards. Furthermore, not all users of a city wayfinding system are tourists; visiting business people, new residents and many others require differing information which relates to their specific needs.

When asking people in the study-site what it is they’re after, the responses were extremely diverse and tended not to include the major landmarks. A user-centred approach has the greatest potential to reveal the actual needs of users and provide a list of destinations that is genuinely relevant for the people who visit and use the site.

Bearing in mind the title of this treatise, the point I wish to make is not just that effective contextual research can lead to better wayfinding solutions, but rather that effective contextual research reveals the limitations of wayfinding solutions.

When synthesising the results of contextual research through the magnifying glass of wayfinding planning, we extract the locational significance of what people are saying they’re looking for and discard the rest. We are then required to develop a taxonomy based on the most common denominator. “I am looking for a decent cup of coffee” will be distilled down and abstracted to something like “Food court” or “shops”. In the process we have lost two layers of specificity; the specific thing and the specific quality.

Wayfinding systems are limited in their ability to satisfy our need to find something specific that exists within a place. However, people are not looking for a destination simply for the purpose of arriving there. On most occasions, we are interested in something that exists within that destination: a specific shop, a specific business, a specific service, a product with specific features or quality. In order to find things, we need a system that facilitates thingfinding, a problem-solving process that is only partially fulfilled by wayfinding.

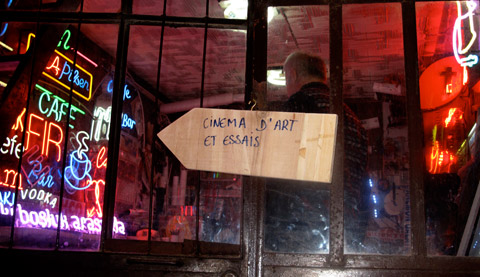

Thingfinding sounds impractical in the context of a wayfinding system, which clearly cannot provide directions to all important destinations, let alone to specific things. However, thingfinding is already a reality, using a growing number of location based services available on smartphones. These range from a basic map application that can display local things around us at greater granularity than any on-street wayfinding system could, through to location based social networks like Foursquare and Brightkite, through which people share qualities of their in-place-experiences. These provide rich metadata about places and things which exist within places. I’ve explained some of these thingfinding services and how they’re replacing wayfinding systems over at ID/Lab’s blog.

Physical and online experiences are no longer discrete experiences – the two are intertwined and the continuum between them is becoming more concrete. We no longer ‘go online’ – we are constantly connected. When connected, we no longer sit statically behind a desktop computer – we move through physical space, creating new associations between our online and offline presence. And we have greater tools and options by which to negotiate our way through physical space.

Online and real-world experiences are blending; so should their design.

Organisations are becoming open to the idea of integrated experience strategies that consider people’s experience across digital and physical space concurrently. One of the barriers to developing and implementing such strategies is the division of responsibilities within an organisation, where for example, the department that commissions digital solutions is segregated from the one which commissions physical solutions. Despite that, it’s becoming apparent that integrated experience solutions are the way of the future.

What others think:

What do you think?

Content :

- Don't judge a book by its cover — — judge it by its spine

- Wayfinding at Design Museum Holon

- The Type Shop

- Issey Miyake pulls Dyson apart

- From Wayfinding to Thingfinding

- Place for words

- DoubleYou Hi

- Mission: Menu

- I Feel Fine, Thank You

- Banalities of the Perfect Home

- The Feltron Report

- Dashanzi Art District

Fred Kent says:

I like the idea of user engagement when developing an urban wayfinding system. You’ve illustrated how the system can’t support the needs of all visitors, but it’s quite controversial not to direct to major destinations. Then again, if the system encourages interpersonal exchange between visitors and locals there’s an opportunity for conversation which might lead to a richer visitor experience. Wayfinding for social good.

29 September 2010Pamela G Parker says:

I really appreciate the idea of giving more thought to the users’ needs, desires and expectations – a wayfinding system begins to support this, and a ‘thingfinding’ system can do more to play on and anticipate new possibilities as well hand over control to the users themselves. What I’m not convinced about is the technology required to gain access to this level of specificity – I’d like to see some examples of a system that has a heightened degree of specificity for its users without relying on them having an iPhone along.

5 October 2010Chris McCampbell says:

You make some great points, and your call for contextual research is exactly what I believe future wayfinding projects need. Current technology allows users to input their own data to create a more personalized experience through a bounty of applications. Future wayfinding, or as I am starting to call it, “waymaking,” will be the result of the user creating their own route based on their own needs and wants. This is vital to creating a strong relationship between person and location.

1 December 2010